1965 – 1972

THE LIONS WIN

And it was in the very next season that Peter Longson’s sunny prediction came to be fulfilled.

Geoff Priestley (not yet the well-loved “Veteran” he has become to many succeeding generations of

Lions) joined the club as a fleet-footed young outfielder, along with his brother Ken, in 1964.

Obviously, the club had travelled far since the Presbyterian Baseball Club had suffered a record

defeat at the hands of Frankston, since Geoff remembers wins against MYF 56-3, and Box Hill 69-0.

Of course, Lions were also on the wrong end of a few drubbings, too; with no ten-run rule, teams

had to play through the pain in those days.

Even as a new member to the club, Geoff knew enough to despise the “mortal enemy”, Cheltenham.

Cheltenham was the dominant team in the late 1950s and 60s, with a “three-peat” for a third straight

A Grade flag in 1960 and a further six flags through the decade. Cheltenham players were known for

“crossing the line”, suffering from “white line fever”, and none more so, according to Geoff, than Lance

Purton. Lance and his brother Keith had played for the Lions, but Lance had decided to defect to the

all-conquering Cheltenham to pursue personal success, leaving behind Keith as a loyal Lion. Lance’s

competitiveness would even tempt him to, what some might consider, the odd bit of skulduggery;

starting pitcher for the Lions from that period, Rod Kingman, remembers how Lance “got in the ear”

of an umpire, who might have been one Rocky O’Brien, rumoured to be happy to share a few beers

before the game with the players. Lance convinced Rocky that Kingman was illegally lifting his foot on

the pitching mound. Kingman was, inexplicably, “continually baulked” until the Lions coach “instructed

me to pitch from the set position.” Showing that it is possible to turn the coat more than once, Lance

Purton later became known as the feared “hanging judge” of the DBA tribunal.

In 1965, Ken Wearne ceded the coaching duties to Bobby Chatto, from metropolitan team

Richmond. The Lions had always sought their coaches from within the ranks of the club. As Kingman

remembers, the players thought they had hit “the big time” in recruiting a coach from a city team. At

a committee meeting, a “discussion on the capabilities, temperaments etc of the players was held

and it was left to Ken Wearne to pass on any information in this regard to Bob Chatto.” So, the club

had certainly evolved since there had been “two chaps to play in every position”, with some

primitive psychological profiling influencing the new coach’s selection philosophy.

Chatto was a hard man who took no nonsense and wanted things done his way, so it’s interesting to

think what he would have made of the cast of characters presented to him – the “enforcer” Col

Carmody, “downright scary” according to some, knockabout Ocker Little, the quieter and more

gentlemanly Peter Longson. And the players themselves had to learn to accommodate Chatto, a

deep thinker, a good tactician, who worked everybody hard, but would always join the players for a

drink or two at the de facto clubrooms, Dandenong’s Albion Hotel. As Geoff Priestley says, it didn’t

really matter what he was he was like; “the only thing we were looking for was to win the

premiership.”

“And that’s what happened.” The 1965 Grand Final loss to arch rivals Cheltenham had stung badly.

Cheltenham had scored six in the first innings, with pitcher Rod Kingman giving up three hits and a

walk, and second baseman Lenny Cahill making an error. Peter Went came on to pitch, and managed

to stem the flow of runs, but another error by catcher Bill Murray proved costly. Murray and Cahill

were to make up for those errors, batting strongly. By the third innings, Cheltenham were leading

eleven to two. But Cheltenham failed to score from there, while the Lions stormed back in the final

three innings, hitting strongly and scoring six. The batters had even outhit Cheltenham. The gap,

though, was too great, and Cheltenham had taken another flag.

In the 1966 replay of the ’65 Grand Final the Lions lined up against erstwhile nemesis, Cheltenham.

Perennial premiers Cheltenham had already ordered a victory cake. This time it was the Lions who

raced to an early lead, scoring five in the first innings, with hits to Wayne Reddaway, Bill Murray, Col

Carmody, Philip Morris and Peter Went. And this time, it was Cheltenham who scored steadily over

the subsequent innings to draw level in the seventh innings at six all. But the wily Chatto had crafted

a plan to lull the Cheltenham hitters, who were expecting to ride out Rod Kingman’s fast balls, and

then take the lead when the ageing Peter Went finished the game out on the mound. But Chatto

pulled Kingman early, leaving him with something in reserve for the final innings of the game. So it

was Kingman Cheltenham had to face up to in the tense final stages of the Grand Final.

The eighth was nerve-wrenching. Ian Campbell opened for the Lions with a double to right-field, but

the next two batters popped up. A walk to Ross Little increased the pressure, but the Lions could not

score, leaving two on base. Things were even more tense in the bottom of the innings, with

Cheltenham’s go-ahead run put out at the plate. In the ninth, the lead-off, pitcher Rod Kingman, hit

safely to centre – the winning run was on base! He advanced on a bunt, but stayed at 2nd base when

Peter Longson hit to centre-field. A walk to Geoff Priestley (who had struck out in his first pinchhitting

at bat) loaded the bases, and Ian Campbell’s sacrifice fly put the go-ahead run over the plate.

And, when Cheltenham failed to respond in the bottom of the ninth, this was the run that gave the

Lions a premiership after twenty-one years of baseball. The Lions generously offered to eat the cake

Cheltenham had ordered. History does not record whether the offer was accepted.

By this time, the Lions were fielding two competitive teams. In 1965, secretary Peter Longson

meticulously recorded in the minutes of the committee meeting that “the position of C Grade

captain was also discussed and it was decided that the election be rigged and Phillip Morris be made

captain” which says much for the commitment of the club officials to accurate record-keeping and

even more about the good-natured wangling that went into running a sporting club in this era.

And the club had not just grown in size or success, but also generationally. While mention is made in

the 1960 minutes of a junior side, organised by G Crabtree, we hear nothing else until the mid 1960s.

By then, many of those early young Lions had grown into family men, and they wanted their sons to

follow in the Lions tradition. Now, we are used to little boys and girls being encouraged to have fun

as T-ballers, then being safely nurtured along a well-kept “pathway” through appropriate graded

levels. Age limits are strictly policed, and we have pitch counts to protect young arms. But in the mid

to late 1960s, the DBA was offering only one age level – U/16. And in order to maintain a viable

competition, teams were allowed to field a certain number of senior players.

So with some of the opposition driving themselves to their “junior” games, most of the Lions players

were too young and too small to compete against much older, much bigger “boys”. In 1965, then,

the Lions’ junior side was made up mostly of players from the Lyndale Cricket Club. Coming from

outside the club, it transpired that the Lyndale contacts were more than a little questionable. “Most

of the Lyndale boys who played that year were ratbags and troublemakers” recalls Michael Wearne.

Michael’s parents did not allow him to play that year, despite vociferous protests from his uncle,

“Ocker” Ross Little, and, no doubt, himself, although he does acknowledge now that “after all, I was

only 7.” Ross Wearne, 9 at the time, and Philip, the son of senior pitcher Peter Went, did fill in at

times during that first season, making up the bare seven players so that the team could take the

field. But after one of the Lyndale players found himself unable to join the team as a result of

believed legal entanglements, the team collapsed, and the committee decided “as far as our Junior

side this year was concerned…to forget about them altogether, and learn from this unfortunate

experience.”

With more Lions to take the field in 1966, the junior arm of the club was properly initiated. Michael

Wearne made his debut (making 2016 his 50th year of baseball), and Ross and Philip were regulars.

There was still only a single junior grade, and the age level fluctuated over the years from U/15 to

U/17. The boys did not win many games in those early years. But the playing list grew. The youngest

Wearne, Stephen, joined his brothers. Robert Koster played. Relatives of senior player Jack Loois,

Albert and Benny represented the club, along with another set of three brothers, the Walshes. When

the Wearne brothers began to recruit some of their schoolmates – Richard Umbers, who grew into a

long-time Lion, Geoff Schonewille, Robert Smallwood and Don Vinall – the Lion cubs began to enjoy

some success. But the Premiership eluded them, finishing runners-up to Chelsea in 1971.

Some early Lion cubs – back row Jeff Ricardo , Ross Wearne, Grant Hubbard, Geoff Schoneville,

Rodney Smallwood, Richard Umbers. Front row Ken Wearne (Coach), Michael Wearne, Ricky

Baker, Alan Wilson, Ian Owen, Stephen Wearne, Don Vinall, Len Cahill (Coach) at the 1971 U/17

Grand Final, Bonbeach.

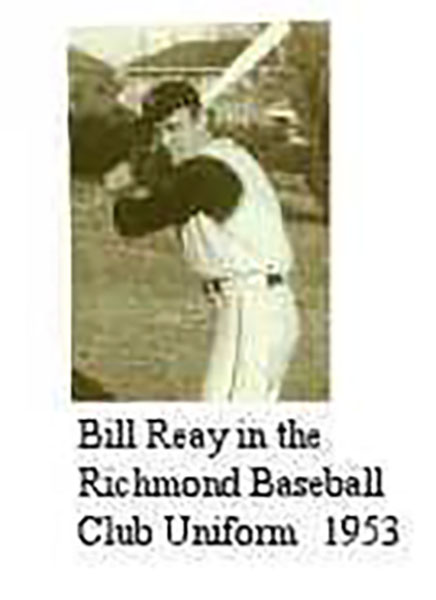

The seniors were also acquiring some valuable recruits. While Bob Chatto coached the Lions to our

first premiership, it was a deal he had made with one of his Richmond team-mates that was to

change our history, bringing to club one of its heart-and-soul life members. Chatto wheedled his

mate Bill Reay into promising that, when he finished at Richmond, he would give the Lions “one

season”. The Lions nearly lost out on that promise, when Bill missed his first game in 1967, because

he couldn’t find Park Oval. Luckily, someone must have clarified the directions for him, since he

played the next week, and the next week…Bill had every intention of retiring at the end of that

promised “one season”, and, nearly fifty years later, with Bill’s name scattered liberally across the

Honours Boards in a myriad of roles, we all know how well he carried out that intention!

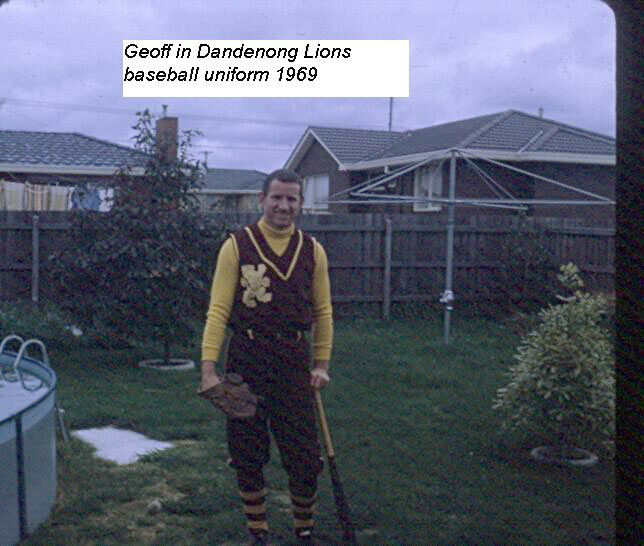

One of the things that struck Bill was the pink uniform in which he was expected to play. It was many

years since the original Lions had been decked out in their resplendent tailored blazers. The older

flannel uniforms were washed out and had faded to a sad dusky pink. And flannel was expensive. In

those days, clubs didn’t go to big-budget sports outfitters. No, the “Ladies” of the club not only

raised the money for uniforms, but Dot Purton and Shirley Wearne purchased material (5 pounds, 5

shillings for enough for 5 uniforms), had it dyed maroon, and then cut out and sewed up the

uniforms. Vinyl yellow lions were stitched onto the brushed nylon, and the outfit was finished with a

yellow skivvy serving as an undershirt, for a stylishly 60s update. By the time buttons were

purchased, we’d moved to decimal currency and the committee approved the further expenditure

of 2 dollars for buttons.

Geoff Priestley modelling the latest in Lions’ style

And it wasn’t only the uniforms that signalled a change in circumstances for Bill. Park Oval was

certainly much more basic than the metropolitan grounds he was used to. The “change rooms” was

a split tree, which survived despite the fact that it also doubled as a toilet. The only cover was a bus

shelter, set in a quaggy dirt patch. The playing surface was pretty much undrained, more like a

paddock than a baseball field, and since games carried on in any and all weather conditions, from

the very soggy to the “very foggy”, winter baseball at the home of the Lions was often a mud-soaked

affair. “Walford’s hole” at shortstop was particularly infamous – or at least, according to Geoff,

that’s what the colourful Frankie Walford blamed for any fielding errors. Right field was short, not so

much a problem, except it was short because the Dandenong Creek ran just behind the diamond. A

two-base hit was in the Creek. Keith Purton remembers that games would be held up while the

creek was searched for missing balls, but the Committee often expressed concern about the number

of balls lost. Obviously, back in 1950 when the Treasurer was buying a single ball at time, not many

two-base hits were heading into the creek.

Most importantly, there were no clubrooms, no place in which players and their families could come

together as a community, no place to hold the shared sense of belonging and identity, no place to hang that 1966 Premiership flag. Of course, the players often congregated at the pub – the Albion in

Dandenong must have seen some hearty Lions’ celebrations. And for occasions that required a little

more decorum, many had opened their homes over the years – Ern and Daisy Wearne began that

tradition with their “end of season” parties. David and Grace Little had hosted committee meetings.

The parents of premiership player Bill Murray often held after-game functions at their Ronald St

home, as did the Crabtrees. Ken and Shirley now had four children, but baseballers were always

welcome even after Roger Clark, a bit unsteady on a mixture of painkillers and beers following a

collision in the field, had stumbled through Shirley’s treasured etched glass doors, and Geoff

Priestley remembers many committee meetings held under the large tree in the back garden. Bill

and Elsie Reay might have been newcomers, and, although team meetings at Bill’s house with Bob

Chatto could become quite heated, the Reay house was a part of the Lions’ fragmented

headquarters.

This was not enough. The club had really outgrown its first home. But where else were we to go? As

far back as 1965, committee member Ian Campbell had noted that the Dandenong Council might

consider building clubrooms, if the club could approach them with 300 pounds. This seems an

unlikely amount of money for the club to raise. After all, it was the Ladies Committee who had had

to raise the 5 pounds for new uniforms. And just two years later, the Committee were so seriously

concerned about the financial position of the club that “it was decided to place a levy of $2:00 on

each member”. After several months, the Treasurer could report that “12 levies had been collected”,

although we were still $0.75 cents short of having enough to pay the bills. Luckily, “another $1:00

was collected, which left us $0.25 cents in the clear.” Still, 25 cents is not enough to start a fund to

purchase “our own land for a diamond.” The Committee continued to ponder the dilemma.

In 1969, Bill Reay had succeeded Bob Chatto as coach. Chatto must have been a very persuasive

man, since when Bill was first urged to take over, he had told his wife Elsie “anyone would be crazy

to take it on”, as the Lions were struggling to field two senior teams. “Anyway” as Bill says, “we

survived that year.”

Still, the club was a family and a home to many. Bill Reay had recruited daughter Gwenda’s

boyfriend Laurie Sherlock to the club. A footballer and basketballer, Laurie must have been keen to

impress Gwenda’s father – he would visit Gwenda at the Reay home in Springvale, then run home to

Dandenong, so signing up for the Lions would have been one more way to convince Bill of his bona

fides. Laurie brought this eagerness to the baseball field, both in training and on the diamond,

always ready to give his best effort. Of course, it was up to Bill to teach Laurie the fine points of

baseball. On one trip away, Bill had to sit Laurie down and give him a stern talking to – Laurie had

bought Gwenda a small memento, and it was up to Bill to make plain to the eager young lover that “

you’re setting a precedent, and the boys are worried. We don’t take things back.”

Obviously, Bill was impressed with the young man, despite his inability to understand the rules of

the end of season trip, and Gwenda and Laurie ended up marrying. Jim Prokhovnik, Springvale Lions

life member was a guest at their wedding: “A lasting memory is of sparks flying at the Registry Office

just before the wedding – when the father of the bride and the marriage celebrant first saw each

other.” The celebrant was Alan Burdett, from the arch adversary Cheltenham Baseball Club, “not a

popular man with any other club”. Jim recalls that “it was quickly agreed (by both of them) that it

would be better for all concerned if another celebrant officiated. This was promptly organised.” The

wedding, though, was during the season. “Bill had invited some of his old Richmond team-mates to

the wedding, and a very long and boozy night of baseball stories ensued at, and after, the reception.

The next day, Dandenong Lions coached by Bill, played Springvale. Not many clear heads prevailed

on either side, and some of Bill’s Richmond mates had stayed around to watch, offer lots of advice to both teams, and drink some more…it was a very long day – Springvale won in extra innings at what

felt like about 9pm”.

The laughter and fun of this day must have seemed very far away just three months later, when

Laurie was diagnosed with a horribly aggressive cancer that had soon invaded his bones. Tenacious

and cheerful, Laurie continued not just to work, but to run to work. And he continued to play

baseball even as he grew thinner and weaker. And he continued to look forward to being a father.

Laurie was in hospital in St Vincent’s when Gwenda went into labour at the Dandenong Hospital, but

an ambulance transported him and he was by Gwenda’s side to hold their newborn daughter, Jodie.

Laurie’s pride and delight in fatherhood lasted only five months before he very sadly passed away.

The shocking swiftness of Laurie’s decline, and the loss of such a bright young man had a profound

effect on the Lions family, but the club knew that Laurie would want the fellowship and the fun to

continue. It was decided to establish a perpetual trophy in Laurie’s name, and to honour his youth,

his optimism, and his development from a newcomer to competitor, the Laurie Sherlock Trophy was

instituted for the Most Improved Player at the club. Notable winners of the Laurie Sherlock Trophy

over the years have been such club stars as Rob Hogan, Myles Barnden, and the nephew he never

knew, Scott Wearne, plus women’s players Shirlie Loon, Maddy Patrick and Gabby Bevan.

Oh, those skivvies. The Lions – back row, John Moon, Bill Murray, Mike Magee, Peter Longson,

Darryl Bray, middle row Ross Wearne, Laurie Sherlock, Bill Reay, Jim Carmody, Dave London, front

row Michael Wearne, Stephen Wearne

But we still did not have an appropriate home ground. Various solutions were proposed: Secretary

Geoff Priestley wrote to the Dandenong Council to discuss the possibility of leasing a shed nearby

Wilson Oval, with the club offering to carry out any necessary renovations; Jack Loois suggested

applying for the Kidd Rd Reserve, which was enclosed and had “amenities” (something hitherto

unknown to the Lions); the Dandenong Workers’ Club was approached for grounds on which to play.

Finally, a sub-committee was formed, with Geoff Priestley submitting finances, Bill Reay focussing on

ground lay-out and John Moon, a cricketer who had never played baseball, emphasising plans to

foster the growth of junior teams. This sub-committee even submitted drawings of the proposed

baseball ground to the Council.

There was to be no new purpose-built baseball ground. But the Council did offer the club space at

Booth Reserve in Clow St, Dandenong. There was even a clubrooms, although a curtain had to be

strung down the middle of the room to modestly reserve a place for “changing only”. With great

excitement, club members set about improving our new home. Bob Chatto had offered an old fridge,

but it was found to be “R.S” according to the minutes of the committee meeting (not the most

official use of language, but probably quite accurate) and a new fridge was purchased for $15. The

Lions eagerly looked forward to holding barbecues after games, planning to sell tickets at 6 for $1.

Now we had a place to hold “pie nights” on all-club victories. Frankie Walford began building a bar,

quite obviously the first consideration in any renovation, and also a locker for equipment. But the

Lions were now a family club, and it was determined by the Committee that “no grog” would be

allowed “in the presence of juniors”. Perhaps this directive was not so strictly policed, as a year later,

Bill Murray again “declared his opposition to drinking in front of juniors.”

And so, in 1972 Geoff Priestley sent a map of our new ground to the other clubs.

It seemed, says Geoff that “we were on a winner”. But after all, the club was there to play baseball,

and so the state of the diamond was key to the success of the move. And Booth Reserve had actually

been a tip, filled in to create sporting fields. There were problems with subsidence. All sorts of things

used to make their way to the surface of the ground. The field was not fit to play on by 1974, and

while the diamond was moved to the north of the oval, the muddiness of the turf wicket meant the

Lions’ home ground was unplayable for part of the season.

Desperate to establish a home suitable to their aspirations, the Lions formulated detailed plans for

improvements to Booth Reserve, including drainage works, the erection of a new net and the

establishment of an all-weather surface, with the luxuries of a pitching mound and proper surfacing

around the bases. Dandenong Council were unenthusiastic, and uncommunicative. When pressed,

the Council admitted that, not only would they not fund or approve the works, but that the Lions

would have to move from Booth Reserve in two years. What was on offer was a hilly portion of

ground in Police Paddocks. But the Lions would need to share this space with the other Dandenongbased

clubs, M.Y.F and Lyndale. And there were no facilities – no changing rooms, showers or toilets,

and no permission for temporary sheds – and it would be at least four years before any plans to

establish such facilities would be considered. The Lions would be more uncomfortable even than

they had been in the dark old days at their first home at Park Oval.

Secretary Geoff Priestley informed members that the Executive would be holding an Extraordinary

Meeting to discuss the future of the Club. Four alternatives were considered. First, the Lions could

accept the offer to move to Police Paddocks and work at levelling the ground – at least there was a

barbeque! Or, the club could ride out the two years at Booth Reserve, while working to make the

Police Paddocks site more suitable for a baseball diamond. It was suggested that some other ground

in the Dandenong area might be found. Committee member Mike Magee was delegated to scout

alternative grounds. Finally, a move to Springvale was mooted. Springvale Baseball Club had a

diamond at Burden Park, with room for another, and clubrooms already set up. It was decided that

Geoff would meet with the Springvale executive to discuss how an alliance between the two clubs

would work, and what each of the clubs would be at the end of that process.

What would this mean for the Lions, a club with nearly three decades of history? The “Pressies” who

had slogged it out on a muddy diamond marked out in sawdust had grown into the Lions in search of

a home that could properly accommodate their ambitions. What story would the future tell?